Zer da Trikitixa?

Trikitixa terminoak oso gauza diferenteak adierazi nahi ditu, genero musikalari, dantzari, genero literarioari edo instrumentuari buruz ari bagara.

Batzuentzat dantza mota bat da, beste batzuentzat musika estilo bat baina gaur egun eta orokorrean tresnari, akordeoi diatonikoari deitzen zaio trikitixa nahiz eta akordeoi diatoniko eta panderoaz egindako bikote instrumentala ere horrela deitzen den.

Bizkaian orain 20 urtetik honako terminoa da trikitixa, filarmonikea erabili izan da Italierazko fisarmoniche-tik datorren terminoa delarik. Etimologiari erreparatuz trikitixa onomatopeia bat da eta onomatopeia hori ez dagokio soinu txikiari, panderoaren soinuari dagokio, trikiti-trikiti-trikiti…

Trikitixa Euskal Herrian

Akordeoi diatonikoari buruzko lehen datu idatzia 1889.urtekoa da. Bertan Juan Carlos Guerrak Urkiolako erromerian kokatzen du “novisimo acordeón edo akordeoi diatoniko berri bat” deitzen duena. Nondik etorri eta zabaldu ote zen berriz, ez dago argi. Bi teoria nagusi daude honen inguruan. Zabalduena, trenbidea egitera etorri ziren Alpeetako langileek (Frantses nahiz Italiarrek) bidez etorri zena da.

Akordeoi diatonikoari buruzko lehen datu idatzia 1889.urtekoa da. Bertan Juan Carlos Guerrak Urkiolako erromerian kokatzen du “novisimo acordeón edo akordeoi diatoniko berri bat” deitzen duena. Nondik etorri eta zabaldu ote zen berriz, ez dago argi. Bi teoria nagusi daude honen inguruan. Zabalduena, trenbidea egitera etorri ziren Alpeetako langileek (Frantses nahiz Italiarrek) bidez etorri zena da.

1890.urtean Altsasun ateratako argazki batean soinu txikia azaltzen da. Beste teoria batzuen arabera zabalkundea Bilbotik Gipuzkoara izan zen. Bilbotik Arratiara, Zornotzara, Gernikara, Lea Artibaira eta ondoren Elgoibarrera, Gelatxoren ingurura eta Eibarrera, Elgetaren ingurura. Zengotita denda Bilbon zegoen, seguruenik Honner markakoak ziren lehen soinuak eta Zengotitak komertzializatzen zituen. Garbi dago akordeoi diatonikoa Europa guztira zabaldu zela XIX.mendearen amaieran, barkoz, trenez eta modu guztietan.

1890.urtean Altsasun ateratako argazki batean soinu txikia azaltzen da. Beste teoria batzuen arabera zabalkundea Bilbotik Gipuzkoara izan zen. Bilbotik Arratiara, Zornotzara, Gernikara, Lea Artibaira eta ondoren Elgoibarrera, Gelatxoren ingurura eta Eibarrera, Elgetaren ingurura. Zengotita denda Bilbon zegoen, seguruenik Honner markakoak ziren lehen soinuak eta Zengotitak komertzializatzen zituen. Garbi dago akordeoi diatonikoa Europa guztira zabaldu zela XIX.mendearen amaieran, barkoz, trenez eta modu guztietan.

Errotzea

Trikitixak berehala hartu zuen leku garrantzitsu bat herri musikako errepertorioa jotzen zuten instrumentuen artean. Arina zen, txikia, eramangarria edozein lekutara erraz eramateko modukoa. Baxuek erritmo bat eramatea ahalbideratzen du, orkestra txiki bat zeukaten soinu tresna bakarrean.

Trikitixak berehala hartu zuen leku garrantzitsu bat herri musikako errepertorioa jotzen zuten instrumentuen artean. Arina zen, txikia, eramangarria edozein lekutara erraz eramateko modukoa. Baxuek erritmo bat eramatea ahalbideratzen du, orkestra txiki bat zeukaten soinu tresna bakarrean.

Baserri giroan gelditu zen erroturik, hirietan bai baitzuten konpetentziarik, bandak, eta beste… Txistulari eta atabalariak Bizkaiko edozein udaletan ordainduak ziren, trikitixa mendi aldeko erromeriatan errotu zen.

Funtzio Soziala

Funtzio sozial ekonomiko bat bazuen trikitixak. Ostatu sagardotegi eta tabernei loturiko trikitilari asko sortu izan ziren, dantzarako aukerak jendea erakartzen baitu. Soinu txikia landa ingurura loturik gelditu zen, erromeriari, hirian kromatikoa zabaldu zelarik gehiago. Herriaren bizimodu arruntean nahiz ospakizun berezietan hartu zuen lekua.

Funtzio sozial ekonomiko bat bazuen trikitixak. Ostatu sagardotegi eta tabernei loturiko trikitilari asko sortu izan ziren, dantzarako aukerak jendea erakartzen baitu. Soinu txikia landa ingurura loturik gelditu zen, erromeriari, hirian kromatikoa zabaldu zelarik gehiago. Herriaren bizimodu arruntean nahiz ospakizun berezietan hartu zuen lekua.

Elementu askatzaile bat ere izan zen. Korronte berri baten moduan hausketa bat ekarri zuen. Trikitilariek soinua jotzen zuten ezkondu arte, ezkondutakoan utzi egiten zuten, ez baitzen oso duina garaiko gizartean trikitilari izatea. Eliza integrismoaren eta errepresio ideologiko handia zegoen garai batean trikitixak funtzio askatzaile bat bete zuen nekazal esparruan. Dibertsiorako askoz ere askatasun handiagoa ekarri zuen dudarik gabe. Elementu aurrerakoia izan zen eta aurre egin zien debeku sozial eta erlijiosoei.

Elementu askatzaile bat ere izan zen. Korronte berri baten moduan hausketa bat ekarri zuen. Trikitilariek soinua jotzen zuten ezkondu arte, ezkondutakoan utzi egiten zuten, ez baitzen oso duina garaiko gizartean trikitilari izatea. Eliza integrismoaren eta errepresio ideologiko handia zegoen garai batean trikitixak funtzio askatzaile bat bete zuen nekazal esparruan. Dibertsiorako askoz ere askatasun handiagoa ekarri zuen dudarik gabe. Elementu aurrerakoia izan zen eta aurre egin zien debeku sozial eta erlijiosoei.

Tradizionala eta berria

Euskal Herrian mende bat baino ez duen trikitixa herrikoia eta tradizional bihurtu dela esan daiteke. Erroa ez da gauza zaharra izan behar, errotu edo sustraitu dena baizik. Trikitixa ez da batere akademikoa izan, herritarra izan da. Lortu duen altxorra herritarra izan da, trikitixak aurreko danbolintero, albokari eta bereziki dultzaineroen errepertorioa hartu eta moldatu egin zuen, dultzainak ez zituen aukerak baititu soinuak. Dultzainak danborreroa behar zuen eta soinuak berriz ezker eskua zuen danborreroaren lana egiteko eta gainera ekonomiari begiratuta ere bakar batek egiten du biren lana.

Euskal Herrian mende bat baino ez duen trikitixa herrikoia eta tradizional bihurtu dela esan daiteke. Erroa ez da gauza zaharra izan behar, errotu edo sustraitu dena baizik. Trikitixa ez da batere akademikoa izan, herritarra izan da. Lortu duen altxorra herritarra izan da, trikitixak aurreko danbolintero, albokari eta bereziki dultzaineroen errepertorioa hartu eta moldatu egin zuen, dultzainak ez zituen aukerak baititu soinuak. Dultzainak danborreroa behar zuen eta soinuak berriz ezker eskua zuen danborreroaren lana egiteko eta gainera ekonomiari begiratuta ere bakar batek egiten du biren lana.

Tradizionala da tradizioz egiten dena, errepikatzen dena. Instrumentuari herriak bere berezitasun propioa ematen dionean bihurtzen da herrikoi, berezko, euskal herri doinu. Kanpoko influentziak geure egiten ditugunean, gure moduan, orduan bihurtzen dira herrikoi eta behin eta berriz errepikatzen badira, tradizional.

Ez bada aldatzen ez da mantentzen eta ez bada mantentzen hil egiten da.

Dantza

Iztuetak 1824an argitaratutako “Guipuzcoaco dantza gogoangarrien condaira edo historia. Beren soñu zar, eta itz-neurtu” liburuan “fandangoa” esaten du, eta Gipuzkoara Bizkai aldetik sartzen ari dela azpimarratzen du: “Gipuzkoan ezta usatzen gizon dantza egin ondoan, ez fandangorik, eta ez Bizkai dantzarik egitea. Egia da orain asi diradena zenbait erritan, bañan nere gazte denboran, dantza beakurtsu edo respetable aietan, etzan bein ere egiten, danza mota oienik”. Iztuetak aipatzen duen Bizkai dantza, arin-arina da. Arin-arina 2/4 erritmokoa eta kasu honetan, kopla kantatuz gero guk “porrusalda” deitzen diogu.

Iztuetak 1824an argitaratutako “Guipuzcoaco dantza gogoangarrien condaira edo historia. Beren soñu zar, eta itz-neurtu” liburuan “fandangoa” esaten du, eta Gipuzkoara Bizkai aldetik sartzen ari dela azpimarratzen du: “Gipuzkoan ezta usatzen gizon dantza egin ondoan, ez fandangorik, eta ez Bizkai dantzarik egitea. Egia da orain asi diradena zenbait erritan, bañan nere gazte denboran, dantza beakurtsu edo respetable aietan, etzan bein ere egiten, danza mota oienik”. Iztuetak aipatzen duen Bizkai dantza, arin-arina da. Arin-arina 2/4 erritmokoa eta kasu honetan, kopla kantatuz gero guk “porrusalda” deitzen diogu.

Trikitixa dantzari loturik ezagutu dugu betidanik, sueltoari eta lotuari. Sueltoa soka dantzaren amaierako zati bat zen. Ordenaturiko dantza batzuen ondoren kaotiko bat zetorren.

Trikitixaren errepertorioa dantzarako piezekin lotu behar da derrigorrez. Suelto edo loturako, azken mendeko erromerietako elementu garrantzitsu izan da soinu txikia. Trikitixak arrakasta izan bazuen ez zen izan jadanik ohiko musika tresnak jotzen zituzten piezak kopiatu zituelako baizik eta dantza lotuari, baltseoari esker, lorturiko errepertorioari esker. Dantza sueltoa bazegoen, dantza lotuarekin izan zuen arrakasta soinu txikiak. Trikitixaren errepertorioaren hiru iturri ere aipa daitezke: karlistadek utzitako musika, musika bandak eta ohikoak ziren instrumentuen errepertorioa.

Trikitixaren errepertorioa dantzarako piezekin lotu behar da derrigorrez. Suelto edo loturako, azken mendeko erromerietako elementu garrantzitsu izan da soinu txikia. Trikitixak arrakasta izan bazuen ez zen izan jadanik ohiko musika tresnak jotzen zituzten piezak kopiatu zituelako baizik eta dantza lotuari, baltseoari esker, lorturiko errepertorioari esker. Dantza sueltoa bazegoen, dantza lotuarekin izan zuen arrakasta soinu txikiak. Trikitixaren errepertorioaren hiru iturri ere aipa daitezke: karlistadek utzitako musika, musika bandak eta ohikoak ziren instrumentuen errepertorioa.

Dantzak neska mutilen arteko harremanak bideratzeko zuen garrantzia ere azpimarratu behar da. Dantzarekin bazegoen kripto hizkuntza bat harremanak egin al izateko. Hortik zetozen neska laguntzeak eta horregatik zegoen gaizki ikusia.

Kopla

Trikitixaren genero literarioa, kopla

Iztuetak 1824an argitaratutako “Guipuzcoaco dantza gogoangarrien condaira edo historia. Beren soñu zar, eta itz-neurtu” liburuan “fandangoa” esaten du, eta Gipuzkoara Bizkai aldetik sartzen ari dela azpimarratzen du: “Gipuzkoan ezta usatzen gizon dantza egin ondoan, ez fandangorik, eta ez Bizkai dantzarik egitea. Egia da orain asi diradena zenbait erritan, bañan nere gazte denboran, dantza beakurtsu edo respetable aietan, etzan bein ere egiten, danza mota oienik”. Iztuetak aipatzen duen Bizkai dantza, arin-arina da. Arin-arina 2/4 erritmokoa eta kasu honetan, kopla kantatuz gero guk “porrusalda” deitzen diogu.

Iztuetak 1824an argitaratutako “Guipuzcoaco dantza gogoangarrien condaira edo historia. Beren soñu zar, eta itz-neurtu” liburuan “fandangoa” esaten du, eta Gipuzkoara Bizkai aldetik sartzen ari dela azpimarratzen du: “Gipuzkoan ezta usatzen gizon dantza egin ondoan, ez fandangorik, eta ez Bizkai dantzarik egitea. Egia da orain asi diradena zenbait erritan, bañan nere gazte denboran, dantza beakurtsu edo respetable aietan, etzan bein ere egiten, danza mota oienik”. Iztuetak aipatzen duen Bizkai dantza, arin-arina da. Arin-arina 2/4 erritmokoa eta kasu honetan, kopla kantatuz gero guk “porrusalda” deitzen diogu.

Azken urteetan trikiti bikoteak ezagutu ditugu, soinu txikia panderoarekin uztarturik jo izan da. Lehen panderistak emakumeak izan omen ziren eta ba omen zen ohitura bitxirik, emakume panderista horietariko batzuek senargaiaren irudia marrazten zuten panderoan. Kopla kantariak ziren. Kopla hauek dantzarakoak, erromeriakoak izaten ziren. Pandero soilez laguntzen ziren hasieran, gerora alboka, dultzaina, bibolina, soinua nahiz beste perkusioren bat ere erabili izan den.

Koplaren testuak zati errepikatuak ditu, dantza berak dituen bueltak bezala. Koplak testu laburrak izaten ziren, puntu biko edo hirukoak, gehienez eta bi erritmo nagusi erabili ohi ziren: binarioa (porrusalda; testu laburrak), eta ternarioa (trikitia, testu luzeagoak). Kopla bakoitzak bere osotasun indibiduala dauka. Bakoitza pieza ale independentea da. Beharbada, noizbehinka, pare bat kopla izan daitezke elkarren osagarri, baina hori salbuespen arraroa da. Kopla bakoitza ale independentea denez, koplariak nahi dituen erara ordena ditzake, zentzurik galdu gabe. Ez dago sortaren garapenik. Dantzarako baliagarriak izatea da hauen funtzioa eta ez istorioak edo diskurtsoak garatzea.

Koplaren ezaugarririk behinena laburtasuna da. Koplen testua laburra denez, elipsi asko eta lotura gramatikalen ekonomia handia dago. Ez dago tokirik betegarrietarako, ezta beste generoetan erabili ohi diren zubi sintaktikoetarako ere. Testu hauek aztertzerakoan sarritan koplak ilogikoak edo inkoherenteak direla badirudi ere logika bisuala da diskurtsiboa baino gehiago.

Trikitixa, soinu diatonikoa

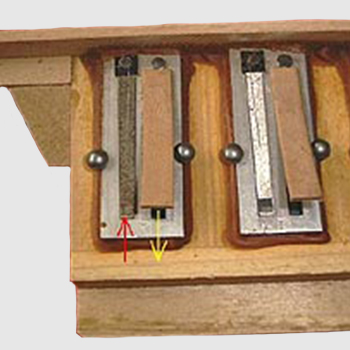

Lengueta

Metalezko xaflatxoa, haizeak dardararazten du soinua atereaz. Somier izeneko egurrezko ohe batean kokatzen da.

Hauspoa

Haizea bildu eta botatzeko balio duen kartoizko sistema.

Somiera

Lenguetak kokatzeko balio duen egurrezko ohea.

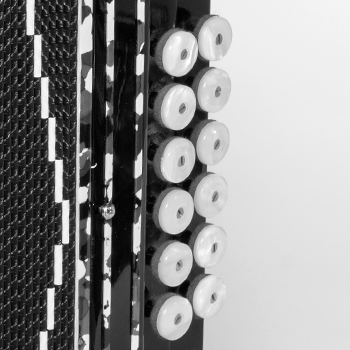

Teklatua

Lenguetak kokatzeko balio duen egurrezko ohea.

Baxuak

Ezkerreko eskuarekin jotzen dira normalean. Botoi bakar batek lengueta desberdinak liberatzen ditu akordeak sortuz.

Ahotsak

Nota bat jotzerakoan dardara egiten duten lengueta kantitatea. Soinu txikiak normalean 3 eta 4 ahotsekoak izaten dira.

Tremoloa

Ahotsen arteko afinazio diferentziak markatzen du. Afinazioa oso zehatza bada, tremolo gutxi duela esaten da. Ahotsen arteko afinazio tarte handiagoa badago tremolo asko duela esaten da.